Rockwell Kent

Mail Service in the Arctic

1937

oil on canvas

83 x 161 in. (210.8 x 408.9 cm)

Commissioned through the Section of Fine Arts, 1934-1943

FA571B

Photo by Carol M. Highsmith

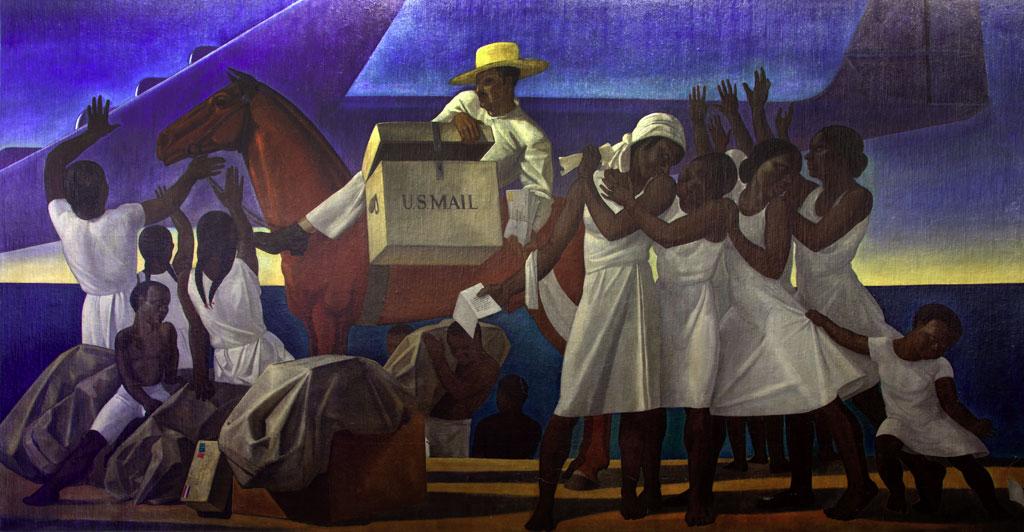

Mail Service in the Tropics

1937

oil on canvas

83 x 161 in. (210.8 x 408.9 cm)

Commissioned through the Section of Fine Arts, 1934-1943

FA571A

Photo by Carol M. Highsmith

At the turn of the twentieth century, Alaska and Puerto Rico represented the northernmost and southernmost territories serviced by the U.S. Post Office Department. Alaska, which had been purchased from Russia in 1867, grew quickly as mining prospectors flooded the territory; they required increased mail delivery via both water and land. Puerto Rico, won from Spain in 1898, necessitated the expansion of United States mail service across an ocean. An avid traveler who had already explored Alaska and visited Tierra del Fuego, Greenland, Newfoundland, and Ireland, Rockwell Kent was a natural choice to depict the importance of the post in these two far-flung locales.

In the 1930s, mail still arrived in Alaska’s ports by ship from Seattle. From there, airplanes commonly transported letters and goods within the state. At each stop, bags were transferred to dog sleds for delivery to their final destinations. Native Alaskans, who were far more familiar with the land and its navigation than recent immigrants, were often hired to drive the dog sleds. This represented a great economic opportunity for a group of people otherwise facing fierce discrimination. In Mail Service in the Arctic, a group of native Alaskans bids farewell to the mail plane. In the foreground, an envelope addressed to Rockwell Kent at Au Sable Forks, New York, changes hands between two women dressed in traditional fur-lined parkas and the driver of the sled.

Depicting mail delivery to the island of Puerto Rico, Mail Service in the Tropics is notable for its rhythmic figures and bold colors. However, when the mural was unveiled, public response did not focus on the technical merits of the mural, but on the text of the letter that the postman delivers to the four women. Relying on his familiarity with Alaskan culture, Kent painted text in the little-known Kuskokwim dialect, creating a fictional message sent from Alaska to Puerto Rico. Translated, it reads: “To the people of Puerto Rico, our friends! Go ahead, let us change chiefs. That alone can make us equal and free.” The implication of revolutionary sentiments angered groups of both American and Alaskan viewers. In Puerto Rico, some viewers objected to the inclusion of only dark-skinned figures. These negative reactions led to an extended public debate that ultimately was left unresolved.

Revolution and Race

Rockwell Kent made his first trip to Puerto Rico in July of 1936, while conducting research for Mail Service in the Tropics. There, he encountered and was distressed by scenes of great poverty, especially among those of African descent. At this time, the Nationalist Party repeatedly clashed with political leaders, including the U.S.-appointed governor, culminating in the March 1937 Ponce Massacre, during which Puerto Rican police killed approximately twenty and wounded over 100 peaceful Nationalist parade-goers. Due to his political and humanitarian sympathies with the Puerto Rican people, Kent chose to depict the dark skinned Puerto Ricans that he encountered during his visit, and to embed in his mural a message of political solidarity.

In September of 1937, newspaper reporter Ruby Black, a friend of Kent’s who had worked in Puerto Rico, published a translation of the text, which was confirmed by another friend of Kent’s, Arctic explorer and ethnologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson. Heated reactions ensued from individuals who interpreted Kent’s inscription as inciting revolution. The New York Times called the murals “insurrectionary propaganda,” albeit ineffective; Rep. Anthony J. Dimond of Alaska wrote to Postmaster General James A. Farley, objecting to the misrepresentation of Alaskan sentiments: “The natives of the Kuskokwim, like other residents of Alaska, are loyal and devoted citizens of the United States, and they have no more intention of making war against the Government of the United States than you and I have.”

Stefansson responded directly to Dimond, noting that the text did not call for violent revolution, merely a change of power. Black also defended the text, writing, “if a great country like America could not tolerate on her walls a mild expression in favor of liberty, Puerto Ricans were all the more right in wishing to have their independence.” Kent, for his part, argued that the aspiration communicated in the letter, the “burning desire for independence,” was an essentially American one.

Nonetheless, Kent offered to replace the text with: “May you persevere and win that freedom and equality in which lies the promise of happiness.” W. E. Reynolds, director of procurement for the Section of Fine Arts, countered with: “To commemorate the far-flung front of the United States Postal Service.” But Kent refused this alteration, insisting on retaining a message of liberty and independence.

Puerto Rican officials, while remaining quiet on the Kuskokwim text, objected to Kent’s inclusion of only dark-skinned men, women, and children. Santiago Iglesias, resident commissioner of Puerto Rico, wrote that the picture did not represent the country or its culture, referring to it as “perverse propaganda against our country;” Rafael Martínez Nadal, president of the Puerto Rican Senate, called the mural an insult due to its depiction of “a bunch of half-naked African bushmen;” the mayor of Ponce, Puerto Rico, described the subjects as “unkempt and uncultured.” In response to this barrage of racist criticisms, Kent offered, provocatively, to revise the panel free of charge to include portraits of members of the Puerto Rican Senate, including Nadal himself if he would agree to model for Kent.

In August of 1938, Puerto Rican governor Blanton Winship requested $3,000 from the Puerto Rican government to remove the Kent mural from the U.S. Post Office Department building, stating that it “is in bad taste and conveys a false impression of conditions in this beautiful island.” Kent assured Ruby Black that the NAACP, the United American Artists, and the Artists Congress would respond, which they did, charging censorship. In the end, the mural has remained unchanged. Kent wrote about the incident: “My simple little trick has given the Nationalist movement more front-page publicity than was accorded to the Ponce Massacre.” Today, the mural continues to testify to the artistic and political passions of Rockwell Kent, as well as to a politically and racially charged moment in the history of the United States and Puerto Rico.

Rockwell Kent (1882-1971)

Born in Tarrytown, New York, Rockwell Kent enrolled in the Columbia University School of Architecture in 1900. At the same time, he studied art under the tutelage of William Merritt Chase. In 1904, Kent left Columbia and enrolled at the New York School of Art. A man of diverse interests, he traveled widely and became a successful illustrator, printmaker, and writer, and also made a name for himself as a political activist. In 1953, Kent testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee; despite denying membership in the Communist party, Kent’s passport remained suspended from 1950 to 1958. In 1960, he gave eighty of his paintings, plus prints, drawings, and manuscripts, to a museum in the Soviet Union. Kent spent the later part of his life operating a dairy farm in Au Sable Forks, New York.

Rockwell Kent is one of eleven artists whose murals are featured in the William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building. Access to the Clinton Building is restricted, however tours are available through the U.S. General Services Administration. For more information, please contact artinfo@gsa.gov.

U.S. General Services Administration

U.S. General Services Administration